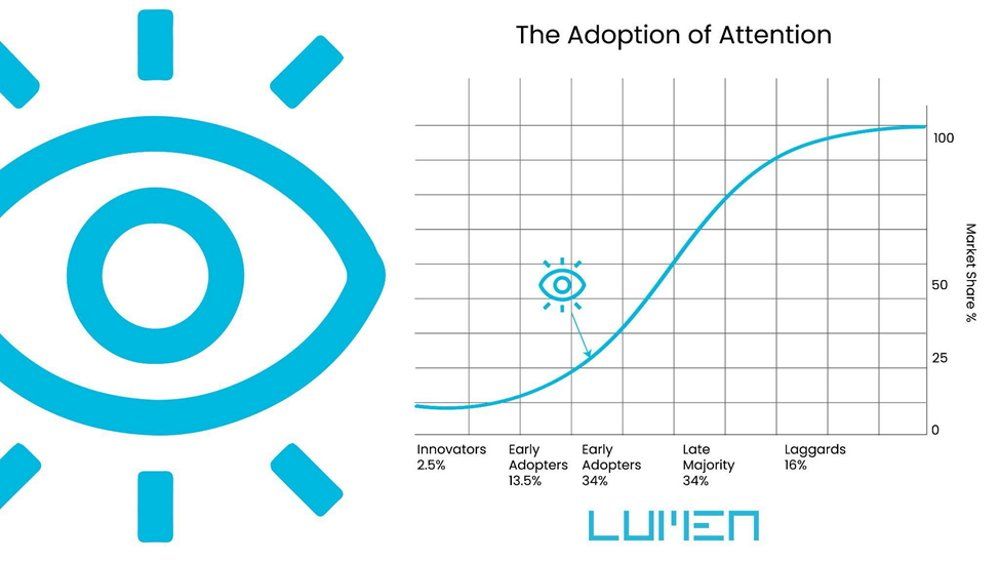

The adoption of attention

Are you an ‘attention innovator’ or an ‘attention laggard’? Perhaps, if you are reading this, you’re more of an ‘attention early adopter’? Heaven help you if you are part of that most despised group, the ‘attention late majority’.

These terms might seem like clichés to you, but they are clichés for a reason. They are terms coined by one of the most influential sociologists ever to have lived, the great Everett Rogers.

Rogers’ The Diffusion of Innovations, which is 60 years old this year, proposes a theory of why some innovations get adopted and others fail. The theory is based on a huge amount of evidence. Its first edition was fantastically robust, reviewing 508 cases of how new technologies or behaviours were communicated and embedded within social systems.

In the five editions since then, and in the literally thousands of studies that have since used the theory, the weight of empirical evidence in its favour has only grown. It has been cited by over 135,000 scientific articles and monographs. This is the sort of law-like relationship that other social researchers can only dream of.

At its heart, it is a theory of how and who: how do innovations get adopted, and who does the adopting. And we can use the theory to analyse the growth of attention data in the advertising industry to understand where we are now and where we may be going in the future.

Let’s start with the who. Rogers recognised that innovation adoption follows an S-curve. At the beginning, innovations are used by self-conscious innovators. These people get a kick out of doing new things or using new gadgets for the sake of newness. But they are not necessarily always very influential: think ‘glass-holes’.

Diffusion really kicks off when really influential users adopt the innovation, the ‘early adopters’. These people aren’t just attracted by the novelty of a new product or approach, but the utility. They judge it by its results, and if the results are good, they benefit disproportionately. The ‘early majority’ look to the ‘early adopters’ to road-test innovations: they are happy to form the large cohort of fast followers. Next come the ‘late majority’: people who are uninterested or sceptical about the new innovation, but who will adopt it once it becomes a default option. At the end come the ‘laggards’, who are often actively opposed to the new way of doing things, and get carried along grudgingly.

Rogers found that the size of the different adopter groups falls on a ‘normal distribution’. That means that, after a relatively slow adoption amongst small numbers of ‘innovators’ and ‘early adopters’, things skyrocket when (and if) the larger groups of early and late majority came to adopt the new approach. He called this the moment of ‘critical mass’, which was in turn popularised by Malcolm Gladwell as the ‘tipping point’.

Where are we on the attention adoption curve right now? It seems that in the UK, and to a certain extent, the US, we are moving from attention being the preserve of ‘innovators’ and ‘early adopters’ to being the province of the ‘early majority’.

Yellow S-curve (we are here)

Time was when people who took attention seriously were lone voices crying in the wilderness. Back in 2013, when we started Lumen, we would meet with agency innovation teams and get very excited by the fact that they were very excited by our technology – forgetting that these people are professionally excitable people. Their role is to gather interesting information for their organisations, but it is often up to others to make the consequential decisions.

A change occurred in 2019, when the decision-makers started getting interested in attention: the planners and buyers, and the client media teams. People like Katie Hartley at Dentsu, Simon Peel, then at Adidas and now at GSK, and Nadia Morozova at TikTok are the definition of ‘early adopters’: critical, questioning, empirical, demanding, serious people whom other people take seriously. They are looking for a new and better way of doing things – but it better be better.

In many ways, the hard work and hard thinking of these ‘key opinion leaders’ has made life much easier for the ‘early majority’ that is now flooding into the attention arena. They still have questions about methodology and technology but there is a feeling that a path has already been cut through the jungle. We’re not always learning things for the first time. In a sense, this makes things less exciting. But it also makes things more dependable. And when you’re talking about millions of dollars, dependable is good.

It may be, then, that we are getting closer to the point of Rogers’ ‘critical mass’ – though we are certainly not there yet. Influential early adopters are seeing great benefits of adopting attention as a means of measuring and optimising advertising. It’s their experience and example that is proving far more compelling to the far larger numbers of ‘early majority’ adopters than any outbound marketing from the likes of Lumen. If this larger group adopt the approach, it is likely to become a default option, and the rest of the market will be swept along whether they care about attention or not.

But this is not inevitable. Rogers’ theory gives just as much insight into how innovations are adopted as who does the adopting. What are the criteria that the ‘early adopters’ are using to make their judgements? Rogers suggested six key areas:

- Relative advantage: the new technology or approach has to be better than the old approach to warrant the hassle of making a change. And attention data does seem to be worth the effort. The Dentsu Attention Economy project showed that attention data predicts brand choice seven times more effectively than mere viewability data.

But Rogers would ask us to broaden our horizons. Innovations are not simply substitutions of alternatives but responses to changes in circumstances. The advertising industry is being disrupted by the death of the cookie: we may not want it, but that’s the way it is. In a world where cookie targeting is no longer allowed or available, alternative approaches such as attention-based contextual targeting suddenly gain disproportionate ‘relative advantage’.

- Compatibility: new technologies get used if they can fit with old technologies rather than requiring new users to rip everything up and start from scratch. Attention data is most successful when it works with the grain of existing practice. Lumen’s data can be embedded within an agency’s planning tools, or deployed as a reporting tag or a buying algorithm within your existing ad tech stack. Ensuring that attention data links to clicks, conversions and brand lift studies is vital for adoption. The surest way to secure the future is to fit in with the past.

- Complexity: innovations that are easy to deploy are also easy to adopt. Lumen’s tags are easy to traffic and our reporting dashboards are easy to read. Traders don’t need much training to make money using the platform. But greater success will come from even greater simplicity.

- Trialability: adopting an innovation is a process of testing and learning. First you might want to apply attention predictions to historic data and match it to historic results. If that makes sense, you might want to apply tags to your live campaigns, and observe the relationship between predicted attention and actual sales. If that works, you might want to skip to the chase, and use a pre-bid custom algo to buy ‘high attention’ media in realtime. At each step, there’s a greater commitment and more risk – but also more reward. Most people therefore take it slow: trialling the approach, calibrating the results, taking stock before taking the next step. If attention providers can support this requirement, trials will become habits, and habits will become assumptions.

- Potential for re-invention: the adopters of a technology often know much more about what it useful for than the providers of the technology. Therefore, the best innovations are ones that the users can reinvent or adapt themselves. It’s important that the technology is flexible enough to admit refinement and repurposing by users. One of Mediacom’s clients told us that they wanted to link attention data to brand lift studies. Was this possible? A quick phone call to the guys at On Device Research, and hey presto: the creation of an attention optimised brand lift study. Innovations that can be added to and repurposed in this way will be much more likely to be adopted.

- Observed results: users have to see the results to see the value. Rogers’ tells the story of Warfarin, the rat poison. Warfarin may or may not be better than alternatives at killing rats, but it does make them very thirsty before they die. As a result, they come out of their holes looking for a last drink, and litter hallways with their corpses. Building supervisors love it because they can see the results of their work. The question for marketers is: what’s your dead rat?

Attention data will be successful not only if it gets results but if it is seen to get results. ‘Observed results’ may mean more than blockbuster conferences and case studies (though everyone is more than welcome to AttentionFest, part of MadFest in July, to hear some of these). In fact, the most compelling observations may be personal and private. The tools and dashboards provided by Lumen allow advertisers to see for themselves, on a daily basis, the impact of using attention data to drive business results.

If attention providers follow these six approaches, the future looks bright for the category. But there are some important headwinds as well.

There are now no serious questions about the relative advantage of attention data over viewability, but there is a question of scope. A measurement system needs to measure all the media that matter so that advertisers can make truly informed decisions. While companies like Lumen can make estimates of attention for Walled Gardens like Facebook and YouTube, our integrations could be better: you can lobby Google for greater transparency and cooperation with Lumen here.

And what about TV, or gaming, or programmatic out-of-home? Attention providers will have to deliver on their promise of a common attention currency across all media to drive deep adoption.

We will have to watch out for competitive responses as well. Already, Nielsen is hassling TVision on seemingly spurious grounds, and DoubleVerify is muddying the waters with their curiously named ‘Authentic Attention’ product. It is only to be expected that the incumbents would try and throttle innovation before it reaches a tipping point, and tips them out of the market.

But if the Attentioneers are equal to these challenges, then we could be on the cusp of a revolution. We have built the proverbial ‘better mouse trap’ (or rat poison). Following Rogers’ theories of diffusion, we are moving from an experimental phase to a mass-adoption phase. Our success will depend on how many influential, important agencies and brands want to adopt the innovation. Are you one of them?

Also published in: New Digital Age

Podcasts powered by AudioHarvest